Project Rationale

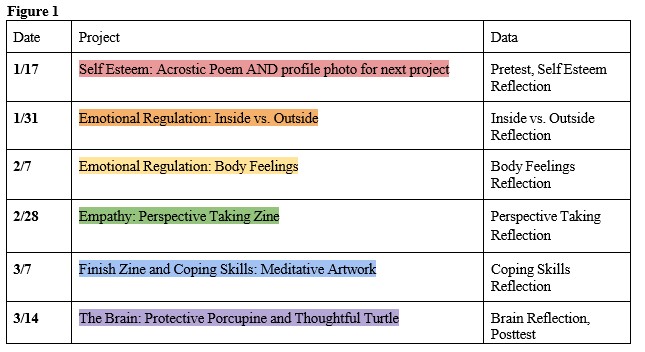

Adolescents are faced with a wide range of stressors including academics, social pressures, extracurricular, and employment. These stressors are dealt with at home, at school, with friends, and online. Greater than 1/3rd of adolescents (aged 10-19 years) have some form of depressive disorder, which has increased from by 14% in the past decade (Shorey, Ng, & Wong, 2022). The need for preventative mental health care in our younger students is clear. Jill Deskin, school counselor, collected data regarding K-5 students' social and emotional needs using minute meetings. This data revealed students have a need for growth in five key areas: Self esteem, emotional awareness, perspective taking coping skills and understanding the brain. As Jill Deskin developed 10-15 minute counseling lessons for each topic, Lindsey Wuest, Science through Art teacher, developed art projects for students to express their understanding of the counseling lessons. Deskin and Wuest formalized the program and instituted it in a quarter-long class for every student in the school. The program Work in Progress, social and emotional learning through art, allows students to create reflective pieces of artwork based on the counseling lesson of the day.

Project Context

Research was conducted at Alexander D. Henderson University School in Boca Raton, Florida, situated on the Florida Atlantic University campus. The study involved 24 fourth grade students, 14 girls and 10 boys, and 24 fifth grade students, and 8 girls and 16 boys. The program, Work in Progress, was instituted during nine classes held on Fridays during quarter 3 of the 2024-2025 school year. The classes were a mix of students from three different home rooms.Each 50 minute class was composed of a short counseling lesson paired with an art activity designed to deepen student understanding of the counseling lesson.

Supportive Literature

The reviewed articles highlight several common themes about social-emotional learning (SEL) and its implications for education. These include the necessity of SEL to address student needs post-pandemic, the role of creative and innovative methods in delivering SEL, and the benefits of SEL in fostering emotional well-being and academic success.

Benitez Esparza (2024) emphasizes that the pandemic disrupted students' social connections, behaviors, and mindsets, necessitating targeted SEL interventions. Schools play a critical role in addressing these gaps, helping students rebuild resilience and engage with peers. McAfee-Scimone (2024) demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating arts into SEL. The EASSEL model enables students to use artistic expression to process emotions and improve interpersonal skills, suggesting that creative methods can enhance engagement and accessibility of SEL programs.

Research consistently supports the long-term impact of SEL. Doré et al. (2017) highlight how helping others regulate emotions enhances self-regulation and reduces depressive symptoms, while Low et al. (2019) document the positive developmental effects of universal SEL programs over time. Despite its benefits, Abrams (2023) discusses the political backlash against SEL, which complicates its adoption. Educators must navigate these challenges to ensure continued access to SEL's proven advantages. According to these documents, we see that schools should prioritize SEL as it fosters resilience and emotional health (Benitez Esparza, 2024). Schools should try to incorporate creative activities like art which can broaden the use of SEL effectiveness. SEL programs should emphasize mutual regulation and empathy building, which benefit not only the individuals but group settings (Doré et al., 2017).

Research Methods

This study used a mixed-methods approach to examine how integrating visual arts into the counseling curriculum impacts 4th-and 5th-grade students' understanding and expression of social-emotional concepts such as empathy, self-regulation, and interpersonal skills.

Qualitative data included class observations noted in research journals as well as open-ended student responses. Students were given a three question pre- and post-test. The pretest was instituted during the first class meeting before any instruction and on the final class meeting after all instruction and art projects had been completed. Students completed open-ended reflections about their artwork the week after completing it.

Pre- and Post-Assessments

- What might you do if you’re experiencing low self esteem? (Low self esteem means feeling bad about yourself.)

- What might you do to better understand the emotions of another person?

- When your brain starts to “flip out” or lose control, what can you do to get back in control?

Student Reflections

- Self Esteem

- When you look at your Self Esteem Name Poem Artwork, what does it make you think about? My Self Esteem Name Poem makes me think about…

- Emotional Regulation

- When you look at your Body Feelings Artwork, what does it make you think about?

- The last artwork we created was the Inside vs. Outside Artwork to help us understand our Did you think about emotions inside vs. emotions outside when you were outside of Work in Progress class? If yes, when?

- Empathy/Perspective Taking

- When you look at your Perspective Taking Zine, what does it make you think about?

- What inspired you to use this situation in your ZIne? For example, if you chose to write about a Fire Drill, why did you choose that as your situation?

- The last artwork we created was the Body Feelings Artwork to help us understand where we feel emotions in our Did you think about body feelings outside of Work in Progress class? If yes, when?

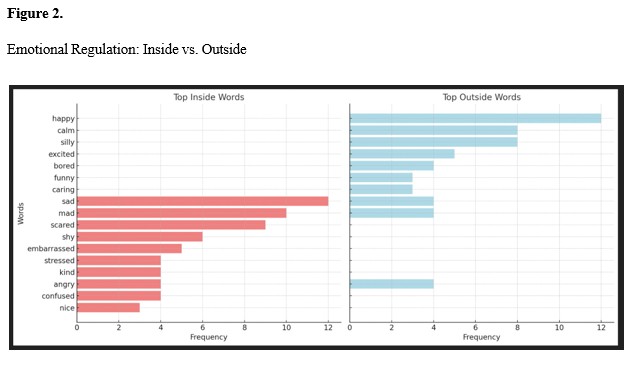

Quantitative data was collected via Likert scale surveys given on the final class meeting. Data was also derived from analyzing student artwork. For example, students created a piece of artwork demonstrating feelings they kept in their heads (inside) versus feelings they feel comfortable sharing with others (outside). Words placed “inside” and “outside” were recorded, counted and compared to determine which emotions students feel comfortable sharing and which emotions they keep to themselves.

Participants

The study involved 24 fourth grade students, 14 girls and 10 boys, and 24 fifth grade students, and 8 girls and 16 boys. The classes were a mix of students from three different home rooms.

Intervention Design

Students in the experimental group received instruction for one quarter (9 weeks), with six 50-minute class periods on Fridays. Each class began with a short SEL lesson on a specific topic (e.g., empathy, self-regulation), followed by an aligned art activity. Students created one piece of artwork per class period, with each piece reflecting a different SEL theme. At the end of each session, students completed a reflection activity to articulate their thoughts and feelings.

Data Collection

This study used standardized SEL assessments that measured changes in empathy, self-regulation, and interpersonal skills. Some example questions were: “What might you do if you are experiencing low self-esteem?” “What might you do to better understand the emotions of another person?” And “When your brain starts to “flip out” or lose control, what can you do to get back in control?” We made classroom observations that focused on students' verbal/non-verbal interactions and emotional expression.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data was analyzed with paired t-tests, and qualitative data (observations, interviews, art, reflections) was coded thematically using AI to identify emerging patterns.

This mixed-methods approach provided both statistical and narrative insights into the impact of visual arts on social-emotional development.

Results

Analysis of the pre- and posttest data for both 4th and 5th grades reveals clear growth in all target areas, strongly supporting the effectiveness of visual arts integration in social-emotional learning (SEL). We saw growth in empathy, self regulation, interpersonal skills, and emotional expression.

Initially, many 4th and 5th graders offered basic responses such as “asking how they feel” or “putting myself in their shoes”. Post program, more descriptive strategies emerged. For example a 4th grader used a 1-5 emotional rating scale, while a 5th grader showed improved emotional boundaries by asking if someone wants space.

Pretests often included passive or deflecting strategies when asked about their regulation skills, such as watching Netflix, or playing games. Postests revealed a shift to intentional strategies practiced in Work in Progress, such as box breaking, meditation, or using art to calm down.

Growth was evident in the student's ability to act supportively interpersonally. A 4th grade student combined empathy with play, while a 5th grade student noted that they would practice active listening with their classmates. Students also added using drawing and creative outlets into their SEL toolbox, as a way to self-regulate their emotions. Students shared they will be journaling, meditating, or coloring as a way to calm themselves.

Implications

The findings confirm existing literature on the benefits of arts integration in SEL. Prior studies suggest that visual arts enhance emotional literacy by providing safe, expressive outlets for their feelings. Our data supports this: students have shifted from emotional avoidance to using creative, mindful practices such as breathing, drawing, and journaling.

Importantly, this study highlights the specific gain in action oriented empathy. Many students advanced from surface-level definitions to engaging in behaviors like checking on friends boundaries or interpreting body language. For educators, the findings show that art is not just enrichment- they are essential tools for emotional development. In an age of rising anxiety and mental health needs, offering students structured, creative ways to process feelings can have a lasting impact. We should be thinking about how to integrate arts into core SEL practices consistently. Educators should also be encouraged to use art as a way to help students name, regulate, and share what really is going on inside.

Resources

Benitez Esparza, Viridiana. "Returning to School After a Pandemic: K-12 School Mental Health Practitioners’ Perspectives Returning to School in Regard to Mindset, Behavior, Performance, and Social Connections." (2024). McAfee-Scimone, Hailey. "Engaging in art to support social-emotional learning (EASSEL): A classroom-based approach." (2024).

Abrams, Z. (2023). Teaching social-emotional learning is under attack. Monitor on Psychology, 54(6), 28. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/09/social-emotional-learning-under-fire

Doré, B. P., Morris, R. R., Burr, D. A., Picard, R. W., & Ochsner, K. N. (2017). Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one’s own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217695558

Low, S., Smolkowski, K., Cook, C., & Desfosses, D. (2019). Two-year impact of a universal social-emotional learning curriculum: Group differences from developmentally sensitive trends over time. Developmental Psychology, 55(2), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000621

Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., & Wong, C. H. J. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 287-305