Project Rationale

Peer-supported learning is a powerful tool in literacy development, particularly in elementary grades where students are building foundational reading skills. Reading partnerships provide opportunities for students to engage collaboratively, allow for peer modeling, and shared problem-solving. One objective of this study is to better understand how these partnerships, whether pairing students with similar reading abilities or pairing above grade level readers with on/below grade level readers, can impact students’ attitudes and confidence toward reading. By examining the dynamics of mentor and same-level partnerships, the aim of this study is to uncover effective strategies for improving reading outcomes in the classroom and provide insights that can inform broader educational practices and reading interventions.

Project Context

Reading partnerships provide opportunities for students to engage collaboratively, allow for peer modeling, and shared problem-solving. There is limited data on how different types of partnerships (mentor vs. same-level) affect both high-achieving and struggling readers. The participants in this study will be the 25 students in my fifth-grade classroom within the FAU Lab School. By conducting this research in my own classroom, I will be able to learn more about myself as a reading teacher. Furthermore, I aim to identify best practices to use when developing reading partnerships and how they directly impact students.

Supportive Literature

Reading as A Social Experience

Although reading is often viewed as an independent task, research has framed it as a social experience, specifically within the context of partnerships. Watkins (2020) explored a reading mentorship program and found that the act of reading aloud with a partner created a shared space for connection and reflection. The students didn’t just read the text, but they also built relationships and learned about their identity as readers. These collaborative interactions extend beyond learning goals and allow students to develop rich emotional connections that make the reading experience more enjoyable. This is especially important in helping to redefine reading for reluctant readers.

Peer Tutoring as a Collaborative Learning Tool

In addition to social engagement, peer tutoring is an effective tool for improving both reading comprehension and students’ confidence in their reading skills. Van Keer and Verhaeghe (2005) found that explicit instruction combined with peer tutoring improved reading outcomes and boosted self-efficacy in students. It is important to note that these gains were seen in both tutors and tutees. This idea is reinforced by Gillies (2016), who highlights that cooperative learning environments, when intentionally designed, enhance motivation and academic growth. These findings suggest that students can thrive when they feel responsible for not only their learning, but also the learning of their peers. In reading partnerships, the mutual responsibility encourages engagement and requires both students to be willing to take risks. Rather than relying solely on the teacher, peer tutoring allows students to develop partnership goals to support each other in feeling empowered to tackle reading.

Research Methods

Intervention Design and Implementation

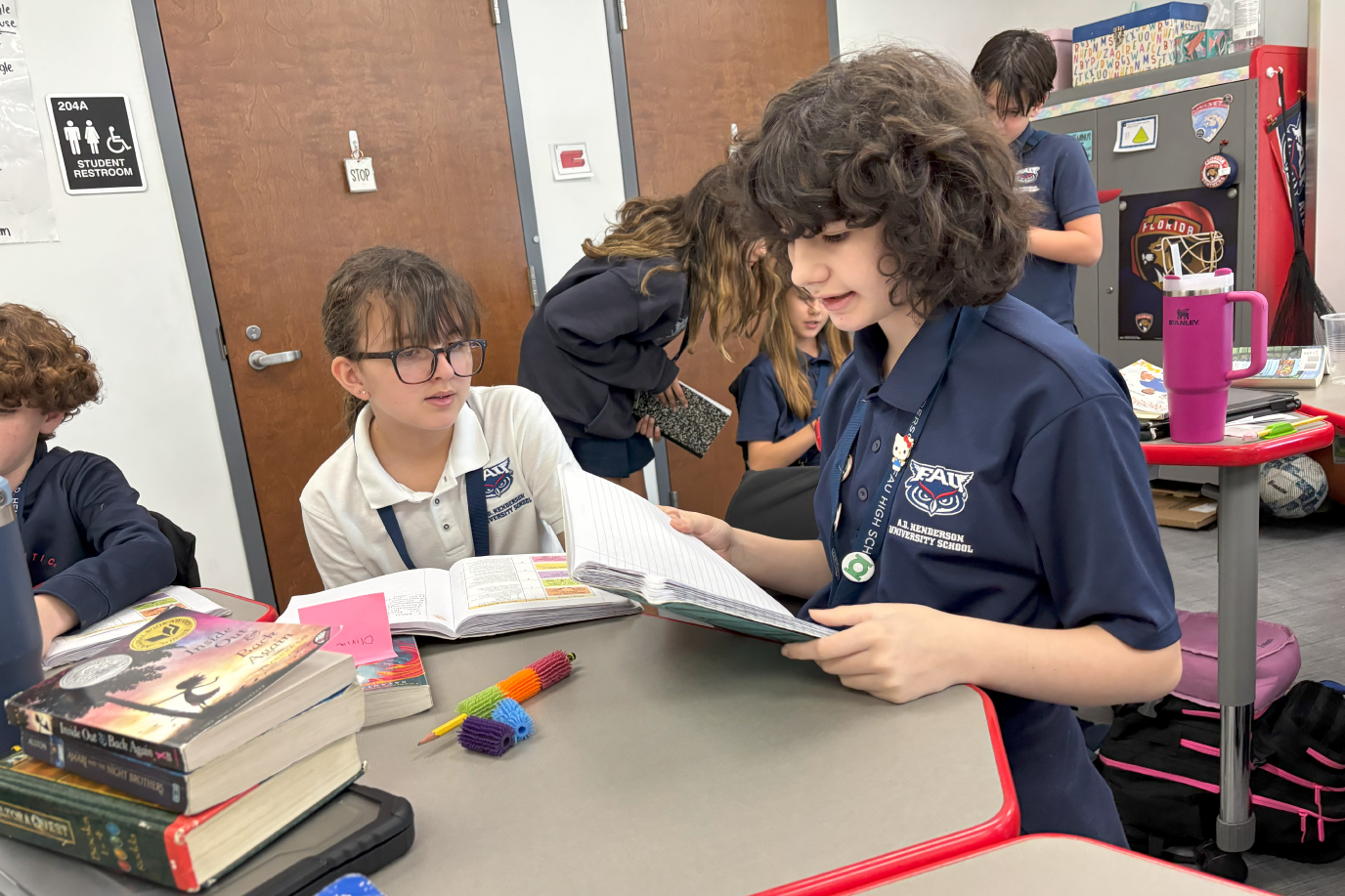

The reading intervention involved the implementation of reading partnerships as a strategy to enhance students' reading confidence and engagement with both fiction and nonfiction texts. For this study, students were paired based on two different structures: mentorship and same-level partnership. In units 1 and 3, partnerships consisted of an above grade level reader paired with an on/below grade level reader. The goal of these partnerships was to foster mentorship, where the higher-level student could support the lower-level student in understanding the material, while the lower-level student brought fresh perspectives and ideas to stimulate discussion. In units 2 and 4, partnerships were restructured with students being paired with others at the same or similar reading levels, either both above grade level or both on/below grade level, to explore the effects of same-level peer interactions on confidence and engagement. The partnerships remained constant throughout each unit, with the only adjustment occurring at the start of each new unit.

At the start of each unit, the reading partnerships were introduced, and clear guidelines were provided to students on how to collaborate effectively. Additionally, the class worked together to develop a shared understanding of what makes a good partner, discussing key qualities such as respect, encouragement, active listening, and constructive feedback. The class created a partnership “buddy” who was drawn and hung on the classroom wall to reinforce the idea of what makes a good partner. At the start of each new partnership, a mini-lesson on partnership skills was administered, and any new collaborative traits the students identified were added to the partnership buddy.

To support the partnerships, students were provided with guiding questions to facilitate their discussions. These questions were specifically designed to align with the reading genre of each unit. For example, in Unit 1, which focused on realistic fiction, the questions addressed themes and elements of fiction. In Unit 2, which focused on nonfiction, the questions helped students engage with factual content, understand text structure, and identify the author's craft. In Unit 3, which focused on nonfiction argument and advocacy, the questions address how to craft a debate and use primary and secondary sources to study a nonfiction topic. In Unit 4, which focused on fantasy, the questions aided students in developing themes, understanding characters, symbolism, and figurative language.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted weekly through surveys, classroom observations, and teacher reflections to assess the impact of the reading partnerships. Weekly surveys were administered through Google Forms to gather students' perceptions of their reading confidence, engagement with texts, and the effectiveness of their partnership. The survey included both Likert-scale questions to measure changes in confidence and engagement and open-ended questions to capture qualitative feedback on the partnership experience. Classroom observations were conducted to monitor student interactions during reading and discussion time. These observations focused on engagement, the quality of peer discussions, and overall partnership dynamics.

Data Analysis

Survey responses were analyzed with a focus on identifying trends in reading confidence and engagement across the partnerships. Qualitative responses were coded thematically to identify common themes related to the perceived benefits and challenges of peer-supported learning. Classroom observations were reviewed to assess the implementation of the partnerships, and a teacher journal was maintained to reflect on the overall process and student progress.

Results

The purpose of this study was to determine how different reading partnerships contributed to the development of students’ reading confidence and peer-supported learning. Through the analysis of data, four key themes were identified in relation to the study’s research question.

Baseline Data Showed Confidence in Reading but Concerns About Partner Work

At the start of the study, students completed a baseline reading survey to assess their reading attitudes, confidence, preferences, and initial concerns about working with a partner. Overall, students reported positive feelings toward reading: 28% stated they loved reading, 40% stated they liked reading, and 28% indicated they were just “okay” with reading. Only 4% of students expressed they did not enjoy reading, but none reported disliking reading. Although students had positive attitudes toward reading, only 12% of students reported that they read daily. 24% of students answered that they read less than once a week or almost never, suggesting that although most of the students enjoy reading, very few engage in it daily outside of school.

Similarly, student confidence levels in reading were also high. 52% of students described themselves as very confident readers who were capable of reading most texts easily. 36% stated they were confident, but sometimes found texts to be challenging, and 12% answered that they were somewhat confident and needed help with certain words or parts.

Students were also asked about their initial concerns related to working with a reading partner. The most common concern, reported by 48% of students, was the possibility of not understanding their book or text. Furthermore, 32% of students reported they were worried their partner might read too quickly or might not be willing to help them. However, 44% of students had no worries about working with a partner at all. These results highlighted the importance of creating an environment that encouraged collaboration and support to help ease the anxieties that nearly half of the students expressed.

Same-level Partnerships Maintain Reading Confidence Levels

Reading confidence improved over the course of the study, though both partnership type and text genre influenced the degree of growth. In Unit 1, which utilized mentor-based partnerships and fiction texts, 76% of students reported improved confidence by the end of the unit. Specifically, 54% of students rated their reading confidence after working with their Unit 1 partner a 5, the highest score possible. Only one student rated their confidence a level 2. This student, a struggling reader, was interviewed immediately after the survey was conducted to determine why they did not feel confident in their reading, and they explained, “I don't feel confident because I’m not really that good at reading… like I don't do well on tests.” This lack of confidence may be due to personal perceptions of poor reading skills, which influenced how they felt about working with a partner. This student's baseline reading data also showed that they do not often read outside of school and prefer to read historical fiction, which also may have influenced their partner work in this unit.

In Unit 2, where students worked in same-level partnerships while reading nonfiction texts, 94% of students rated their reading confidence a level 3 or higher, but only 48% of students rated themselves a level 5 after working with their partner. This suggests that nonfiction texts without mentor support may pose challenges for struggling readers. One student reflected at the end of the unit, “I mean it’s like a 50/50 split for me because he taught me stuff but like didn't at the same time.” This reflection highlights that although the partnerships provided some level of support, it was inconsistent or incomplete. While mentor-based pairings offered scaffolding for some students, the effectiveness of the support was dependent on the mentor’s ability to consistently engage with their partner. This shows that while mentor-based partnerships can foster growth, they can also result in uneven learning experiences where partners may not get the individualized support they need based on their ability.

In contrast, in Unit 3, which also involved nonfiction texts but grouped students into mentor-based partnerships, reading confidence was at its lowest, with 35% of students rating their confidence a 2 out of 5. By the end of the unit, only 9% of students rated their reading confidence a level 5. Although there were lower levels of reading confidence during this unit, 87% of students reported that their partner helped them learn something new and understand the reading sessions more effectively. For example, one student explained that by the end of unit 3 their partner “helped me focus more and helped me learn more on a passage and why the answers make sense,” indicating that the mentor role was valuable in supporting comprehension skills, even if it did not immediately boost reading confidence. Another student mentioned that their partner consistently “helped me when I was stuck,” suggesting that the partnerships provided a crucial support system for navigating challenges in the text.

Preliminary data from Unit 4, which involved fiction texts and same-level partnerships, indicated consistently high reading confidence levels. By the end of Unit 4, 96% of students reported feeling confident in their reading. Data is still being collected from this partnership. Overall, although both partnership types supported reading confidence, same-level partnerships appear to maintain confidence more consistently, especially when paired with fiction texts. When students were asked which partner was the most beneficial to their learning throughout the school year 61% of students preferred their same level partners over their mentor-based partnerships. Interestingly, 78% of the students who preferred their mentor-based partners were identified as low-level readers at the start of the school year.

Partnerships Aid Students in Developing Collaborative Skills

Students' reflections revealed notable growth in partnership skills over time. After providing mini lessons on effective partnerships at the beginning of the year and at the start of each new partnership, students emphasized the importance of good partnership skills in their reflections. After Unit 1, students emphasized that their partners displayed good partnership traits including listening, which was mentioned 10 times, and non-verbal communication such as body language, mentioned 3 times. Students commented, “We listened to each other very well,” and identified areas for growth, such as "thinking a little deeper about what we talk about." By the middle of the year, students continued to prioritize listening (mentioned 11 times) and began to emphasize understanding (mentioned 3 times) as critical elements of successful partnerships. One student noted that their partner was "always listening to me and never talking over me," reflecting a growing respect for collaborative dialogue.

By the end of the year, students demonstrated deeper collaborative skills. Listening was cited 12 times and helping was cited 10 times as key attributes shown during their partner meetings. Students reflected that "they listened to me well, and that makes me want to listen better" and "they helped me be a better partner." When asked what they learned about themselves, students expressed growth in both academic and personal spaces, stating, "I learned I have potential," "I can expand my thoughts," and "to listen no matter what." These reflections suggest that peer-supported learning evolved from basic listening skills to more sophisticated academic collaboration over the course of the year.Overall, these findings show that while both partnership types contributed to student growth, same-level partnerships paired with fiction texts most consistently supported reading confidence. Additionally, students developed increasingly sophisticated collaborative partnership skills over time, highlighting the broader impact of peer-supported learning beyond reading comprehension alone.

Implications

The results of this study suggest that meaningful pairing of students in reading partnerships is essential to supporting reading confidence and comprehension. While mentor-based partnerships offered targeted support for struggling readers, same-level partnerships provided a consistent confidence boost among most students. This finding emphasizes that educators should reflect on their pairing structures and remain flexible. Rather than adopting a single model, it is important to do what is most beneficial for diverse student needs.

Furthermore, this study highlights the benefits of reading partnerships beyond academic growth. Over the course of the school year, students were able to develop strong partnership skills, which are essential as they continue through school and into adulthood. These peer-supported interactions evolved from basic cooperation to meaningful dialogue, empathy, and self-awareness. This has important implications for classroom practice. By utilizing structured peer interactions in reading instruction, educators can simultaneously support literacy development and collaborative learning skills.

References

Gillies, R. M. (2016). Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 39-54.

Van Keer, H., & Verhaeghe, J. P. (2005). Effects of Explicit Reading Strategies Instruction and Peer Tutoring on Second and Fifth Graders’ Reading Comprehension and Self-Efficacy Perceptions. The Journal of Experimental Education, 73(4), 291–329. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.73.4.291-329

Watkins, V. (2020). Reading collaborative reading partnerships in a school community. Changing English, 27(1), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2019.1682966