Project Rationale

The introduction of new programs often generates excitement among those who initiate the implementation. However, it's essential to consider all stakeholders in the process. Teachers, who are on the front lines of implementation, are frequently excluded from decisions surrounding program adoption. Multiple studies have demonstrated that teacher buy-in is critical to the success of any new program (Ravitch, 2010; Fullan,2010; Lee & Min,2017 ). However, less attention has been given to the importance of student buy-in. In the case of a character education program like Character Counts!, student understanding is especially crucial, because the program aims to shape students’ character, social-emotional development, and academic skills (Character Counts!). If students do not understand the purpose of the program, they are unlikely to fully engage, limiting the program’s overall impact. The study hopes that student engagement will increase as a result of increased autonomy on Character Counts activities. This study aims to examine students’ understanding of the Character Counts! program, beginning with their comprehension of character education and gradually moving into the specifics of the CC! Program.

Project Context

Research was conducted at A.D Henderson University school on the Florida Atlantic University campus. AD Henderson is a public lab school located in Boca Raton, Florida. The study involved 22 6th grade through 8th grade students taking a course titled Service Learning. Overall, the sample was 27% male and 73% female. Notably, half of the participants (50%) were 7th grade students, while 32% were 8th graders and 18% were 6th graders. The predominance of 7th and 8th grade students is significant because these students were previously exposed to the Character Counts! program at the middle school level.

Supportive Literature

Student engagement is a crucial component of any successful school program, yet much of the research has focused more on teacher buy-in than student buy-in. While teacher buy-in plays a key role in successful implementation of initiatives, it is important to understand how student choices, and engagement impact the process. Especially if the program like Character Counts relies on students participation and buy-in to make a difference in the school community. This study explores the connection between student buy-in, choices, and behavioral engagement within the context of the Character Counts! Program.

Student Buy-in and Engagement

Research on teacher buy-in is extensive. According to Lee and Min (2017), teacher buy-in is made up of a teacher's "perceptions, beliefs, and values in relation to the reform program" (p. 372). Achieving "teacher buy-in" goes beyond a teacher's acceptance of a new program; it means a teacher is included in the decision-making and is invested in the program. Teacher buy-in is essential for a program's success. However, less is known about the connection between student buy-in, student engagement, and program success. Cavanagh et al. (2016) studied undergraduate students' buy-in in an active learning science course. Cavanagh et al. (2016) define student buy-in as "describes individuals' feelings in relation to a new way of thinking or behaving” (p. 2). Their study found that students who bought into the active learning model showed higher levels of engagement in the course; thus, buy-in leads to engagement (Cavanagh et al. 2016). Fredricks et al. (2004) use the words investment and commitment interchangeably when speaking of engagement. Fredricks et al. (2004) examine three engagement types: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive. This study focused on behavior engagement, defined as "participation in school-related activities" (p. 62). Similarly, Carini et al. (2006) explain that the National Survey of Student Engagement measures engagement by looking at "the extent to which students devote time and energy to educationally purposeful activity" (p. 4). Understanding the relationship between buy-in and engagement is important for the success of the Character Counts! Program.

Student Choice

The word choice carries a positive connotation, but in the academic area, choice is not always an option. Many schools follow a prescribed curriculum, and students are required to follow said curriculum. Allowing students a choice, even a controlled choice, may solve a stagnant environment. Instructional choice is often referred to as a "low-intensity strategy" because it is easily implemented in a classroom. Enis et al. (2018) define instructional choice as "a flexible strategy for use as an antecedent or consequence defined as an individual choosing between two or more activities under specific conditions" (p. 78). In the case study of two elementary students, Lane et al. (2015) examined students' academic engaged time (AET) when exposed to across-task choices and within-task choices. Lane et al. (2015) found that in one student, there was a "functional relation between the introduction of across- and within-task conditions and changes in AET" (p. 497). Additionally, the disruptive behavior of that same student also decreased. However, there was no significant relationship with the other student. In a case study of three third-grade students, Ennis et al. (2020) measured the effect of choice on the variable "AEE," defined as "actively engaging in academic responding" (p. 84). Ennis et al. (2020) study resulted in a mixed picture; for two students, there were minor increases, but for one student, they "displayed significant increases in AAE" (p. 89). Flowerday and Schraw (2023) examined the effect of choice on undergraduate students' cognitive task performance and affective engagement, which they define as students' attitude toward the course. Their findings reveal that "choice did not increase cognitive engagement" (Flowerday & Schraw, 2023, p. 212). However, there was an increase in students' affective engagement leading the authors to recommend further research to study how choice or "perceptions of choice" impact students' intrinsic motivation (p. 214). In line with this recommendation, Spinney and Kerr (2023) examined undergraduate students' views on choice-based assessments and found "that students were highly receptive to their experience with the choice-based assessment strategy" (p. 51). Additionally, Spinney and Kerr (2023) included questions to "measure the purported benefits of choice-based assessment and the domains of student engagement" and found a positive relationship (p. 53). Similarly to Spinney and Kerr (2023) this study focused on students' perceptions of choice in regards to Character Counts! activities.

The research reviewed suggests a meaningful relationship between student buy-in and engagement. Additionally the research shows that even small opportunities of choice can lead to increased investment from students. These findings support the inclusion of student perspectives in the implementation of programs like Character Counts!.

Research Methods

This study was conducted from September to March during the 2024-25 school year. To begin the study, students completed a pre-survey via Google Forms to assess their baseline understanding of character education and the Character Counts! program. The survey included both Likert-scale questions, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and open-ended response questions.

Open-Ended Questions:

- Provide your definition of Character Education

- In your own words describe the purpose of the Character Counts Program (why are we using it)

Throughout the study, students completed two exit slips to assess their perspectives on the Character Counts activities they were leading. Student completion rates on these exit slips were also tracked as a data point. The study concluded with a post-survey, which was compared to the pre-survey results to evaluate changes in students' understanding and opinions of the Character Counts program, with particular attention to whether providing choice increased their comprehension of the program.

Results

Finding One: Students’ understanding of the definition of Character Education and purpose of the Character Counts program increased from the pre-survey to the post-survey.

Based on the responses to questions from the pre-survey and post-survey, definitions of character education were more redefined. Students in the pre-survey used uncertain language such as “I think,” and some students even expressed no knowledge by answering “I don’t know”(see Figure 1). In contrast, on the post-survey, all students provided clear definitions and an accurate definition of character education.

The growth in students' response between the Pre and Post Survey is clear when analyzing individual responses (see Table 1). For example, Student 1 explained that they did not like the Character Counts! Program but was honest and admitted that they did not know much about the program. After the implementation of the program, Student 1 was able to clearly define the purpose of the Character Education.

When asked to explain the purpose of the Character Counts! program, four students in the pre-survey used uncertain language such as “I think” and “I believe,” but this language was not used in the post-survey (see Figure 2). Once again this contributes to the success of the implementation of character counts activities. The activities increase students' ability to clearly articulate the purpose of Character Counts!.

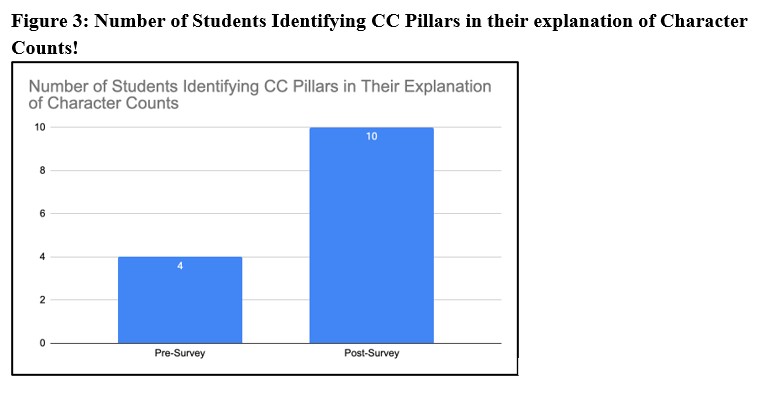

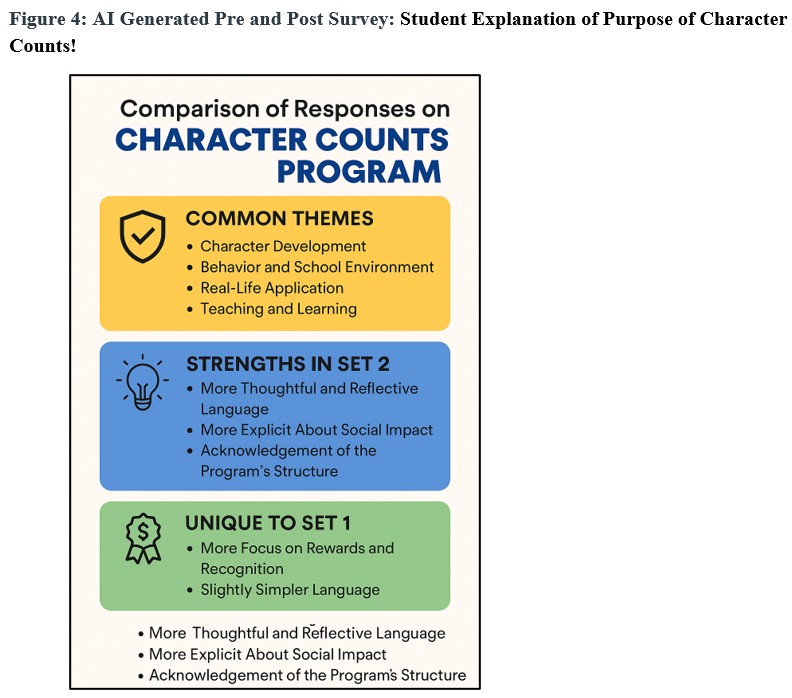

Additionally, on the post-survey, ten students mentioned the Character Counts Pillars in their explanation of the purpose of character counts; this was a significant increase from the pre-survey (see Figure 3). This illustrates an increase in students' understanding of the Character Counts! program, which is based on six pillars. To further support these findings, the researcher used the AI program ChatGPT to analyze the Pre and Post data regarding students' explanation of the purpose of the Character Counts! Program (see Figure 4). ChatGPT's analysis reinforces the positive development of students' responses from the pre-survey (Set 1) to the post-survey (Set 2). Post-survey responses demonstrated more reflective language and emphasized the program's impact on student's lives, whereas pre-survey responses focused more on external rewards.

Finding Two: Students reported positive attitudes toward the Character Counts after participating in program activities.

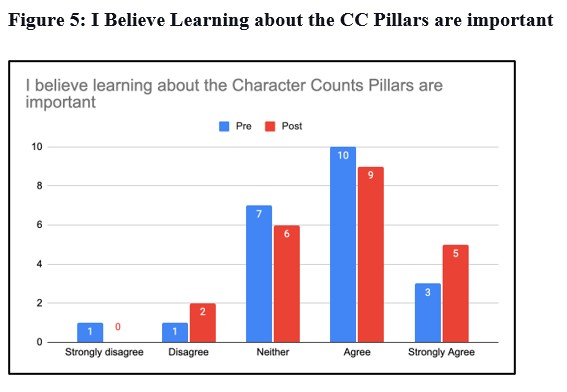

Students' post-survey data and the researchers' journal notes indicate students' positive attitudes in participating in Character Counts activities. In the pre-survey & post-survey, students were asked if they believed learning about the CC pillars was important (see Figure 5). Based on pre-survey results, the average response using a Likert scale of 1 to 5 was 3.64, and the post-survey average was 3.77. The data also shows that 100% of students maintained or improved their ratings. These results show a positive shift in students' perception of the importance of Character Counts pillars after participating in CC activities.

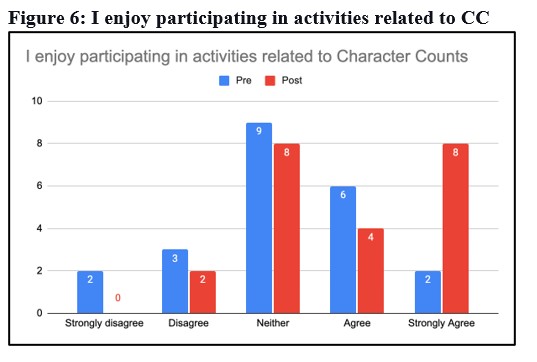

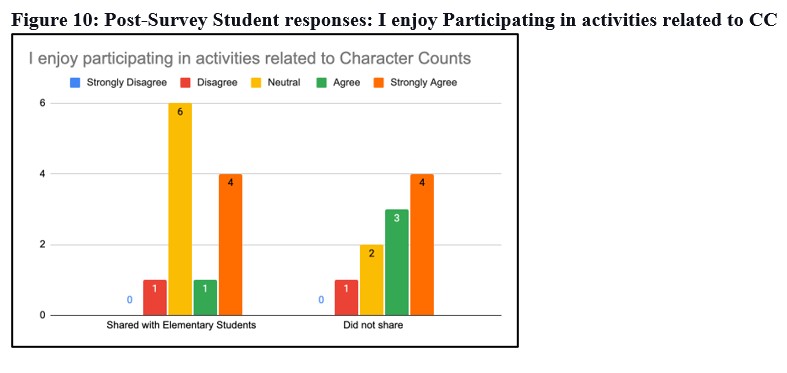

For the question "I enjoy participating in activities related to Character Counts," the post-every average was 3.81, in contrast to the pre-survey average of 3.13 (see Figure 5=6). Notably, students who gave the top rating of 'Strongly Agree' increased from 2 to 8 from pre- to post-survey. Once again, the growth in responses from pre and post-points to students' enjoyment of the Character Counts activities. Students' open responses on the post-survey and feedback in the focus group indicate a positive attitude towards the Character Counts activities they participated in. The researcher recorded students stating, "I like working with Kindergarten" and asking, "Can we do it again?". The word "fun" was also recorded in the focus group. In total, 12 out of 22 students shared an original Character Counts activity with elementary students. These students formed the focus group, and 100% of their responses were positive.

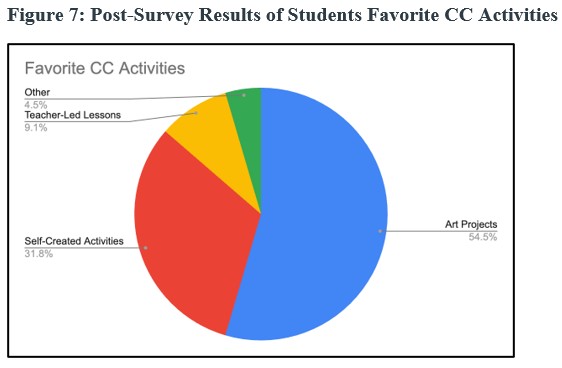

In the post-survey, students were also asked to identify their favorite activities and explain their responses. The results showed that students enjoyed the Art Projects the most, with 54.5% of students selecting that option (see Figure 7). Self-created lessons followed closely behind, chosen by 32% of students. These findings suggest that creative and student-centered activities may enhance engagement and overall satisfaction with the program.

Based on students' explanations of their favorite activity choices, the researcher identified four recurring themes across the responses: collaboration with peers, hands-on learning, teaching others, and fun (see Figure 8). For example, when coding the data, anytime a student mentioned using their hands for an activity, such as stating "doing arts and crafts," this was coded under the hands-on learning theme. Some responses were coded under two themes. For example, the student response, "When I create activities with friends, it's fun, and we get to work together," was coded under the themes of collaboration with peers and fun.

Finding 3: Student participation in the Character Counts Ambassadors program did not demonstrate a measurable impact on overall student engagement with or commitment to the Character Counts initiative.

Students who participated in this study were offered to be Character Counts Ambassadors to increase engagement and buy-in. However, the data shows no statistically significant relationship between groups who participated in the activity and those who did not participate in the activity (see Figure 9). In the post-survey, when asked, "Participating in Character Counts Activities helps students (including me) understand the program," students who shared their activities with elementary students were more likely to strongly agree or agree than those who did not share. The group that did not share had a higher percentage of students who answered "neutral or disagree."

On the post-survey, when asked, "I enjoy participating in activities related to character counts," students who did not share responded more positively when compared to students who shared with elementary students (see Figure 10). The most notable difference is that students who did share had significantly more neutral responses. This may suggest that the experience of sharing with younger students introduced more complex or mixed feelings about participation.

Implications

In the study, all students were required to participate in Character Counts activities, which led to increased participation in activities and understanding of the program. While these outcomes align with expectations, they highlight many students' lack of knowledge of the goal of the program. Although we are in year three of implementation, many students were not able to identify the purpose of the Character Education program. The school needs to take the time to help students internalize the program's values and find the best way to do this. Students' perspectives and leadership are essential. Program implementation often fails because it is a top-down mandate. Individuals are expected to participate without input, which leads to unauthentic participation.

Moreover, while sharing can be empowering, it can also create pressure or anxiety for some students. It is possible that they did not feel confident in their role as ambassadors. These mixed reactions further emphasize the need for students to have a deeper connection to the program and a voice in how it is implemented. More research is required to understand student perceptions of being part of the ambassador program.

References

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9

Cavanagh, A. J., Aragón, O. R., Chen, X., Couch, B., Durham, M., Bobrownicki, A., Hanauer, D. I., & Graham, M. J. (2016). Student buy-in to active learning in a college science course. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 15(4).

Ennis, R. P., Lane, K. L., & Oakes, W. P. (2018). Empowering teachers with low-intensity strategies to support instruction: Within-activity choices in third-grade math with null effects. Remedial and Special Education, 39(2), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932517734634

Ennis, R. P., Lane, K. L., Oakes, W. P., & Flemming, S. C. (2020). Empowering teachers with low-intensity strategies to support instruction: Implementing across-activity choices during third-grade reading instruction. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22(2), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300719870438

Flowerday, T., & Schraw, G. (2003). Effect of choice on cognitive and affective engagement. The Journal of Educational Research (Washington, D.C.), 96(4), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670309598810

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. Retrieved from https://go.openathens.net/redirector/fau.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/school-engagement-potential-concept-state/docview/214138084/se-2

Lane, K. L., Royer, D. J., Messenger, M. L., Common, E. A., Ennis, R. P., & Swogger, E. D. (2015). Empowering teachers with low-intensity strategies to support academic engagement: Implementation and effects of instructional choice for elementary students in inclusive settings. Education and Treatment of Children, 38(4), 473–504.

Lee, S. W., & Min, S. (2017). Riding the implementation curve: Teacher buy-in and student academic growth under comprehensive school reform programs. The Elementary School Journal, 117(3), 371–395. https://doi.org/10.1086/690220

Spinney, J. E. L., & Kerr, S. E. (2023). Students’ perceptions of choice-based assessment: A case study. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v23i1.31471