Project Rationale

Initially, the project aimed to foster a growth mindset among students; however, it quickly became evident that this focus was not addressing the most immediate barrier to student learning: student apathy. Many students displayed a lack of motivation that could not be overcome through mindset interventions alone. As a result, the project's trajectory shifted to directly target student engagement and motivation. While the overall goal of closing achievement gaps remained unchanged, the revised approach prioritized re-engaging students by addressing their lack of intrinsic motivation. The research pivoted to strategies that emphasized student autonomy and the use of extrinsic motivation, recognizing that students needed tangible incentives to participate meaningfully in their math coursework. Understanding students' perceptions and goal-driven behaviors became central to developing effective interventions that could reignite their interest and effort in learning.

Project Context

This research was conducted in a Public K-8 school with a total student population of 247 within the middle school. The focus group consisted of 16 7th-grade math students, including seven males and nine females, all working at grade level. The remaining 66 students in the grade are enrolled in advanced math, performing one or more levels above. As a result, the focus group is categorized in the lower quartile for math within the school context, although none of the students failed the state assessment in the previous year.

Supportive Literature

Many studies have contributed to understanding how mindset, perception, and instructional design influence student outcomes. Dweck (2006) introduced the fundamental distinction between fixed and growth mindsets, providing the foundation for subsequent studies. Recent studies by De Kraker-Pauw et al. (2022) have explored how students' perceptions of intelligence influence their academic trajectory. Mabry (2022) extended this discussion by emphasizing the role of student perspective in motivation and success, particularly in marginalized populations. His work underlines the importance of fostering empathy and understanding within educational environments. Watson (2019) built on these concepts by advocating for a learning growth model that stresses continuous intellectual development through effort and adaptability.

Geary and Xu's (2022) research suggest that schools exist to teach biologically secondary skills. Since children are not naturally motivated to learn these subjects, teachers need to employ extrinsic motivators to engage students. Extrinsic motivation, such as rewards or grades, can provide the necessary push for students to engage in learning these non-instinctive skills. Over time, if students are supported in their learning through positive reinforcement and autonomy, they may develop more intrinsic motivation. This aligns with self-determination theory, which emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in promoting internalization of learning and long-term engagement (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009).

Together, these studies offer valuable insight into the critical role that mindset and motivation play in education. When combined with Geary's research on primary and secondary knowledge, they form a strong theoretical foundation for action research. Geary's work highlights that intrinsic motivation may not naturally extend to academic subjects, particularly those requiring abstract, non-survival skills, underscoring the need for purposeful intervention. This perspective supports the use of extrinsic motivation strategies to foster engagement, build self-efficacy, and ultimately strengthen a growth mindset. Research by Niemiec and Ryan (2009) further reinforces that when students' psychological needs are supported, especially through autonomy and meaningful goals, they are more likely to internalize motivation and experience academic success. This body of research offers a well-rounded framework for understanding and influencing student motivation, making it an essential guide for educators seeking to improve academic outcomes through targeted, evidence-based strategies.

Research Methods

Data Collection

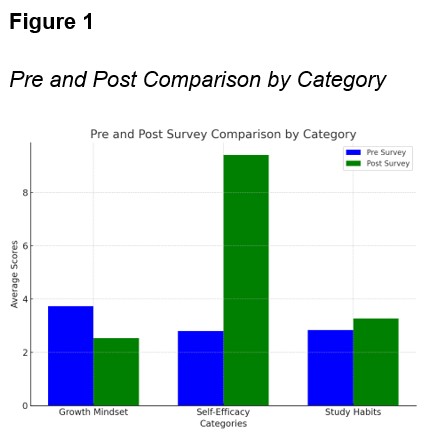

A pre-survey and post-survey were administered using an Academic Self-Concept Survey to assess student motivation and engagement shifts. While the survey was originally selected to focus solely on measuring growth mindset, it was later adapted to support the revised focus of the action research, student motivation, and engagement. Questions were narrowed down to focus on three core categories: growth mindset and effort, self-efficacy and academic self-concept, and study habits and preparedness. Questions targeting a growth mindset explored beliefs about effort and success, such as "If I try hard enough, I will be able to get good grades" and "Most of the time, my efforts in school are rewarded." Items related to self-efficacy examined how students perceive their abilities, with statements like "I believe that my teachers want me to succeed" and "I feel that I do not have the necessary abilities for certain courses." Study habits and preparedness were assessed through responses such as "I have poor study habits." In addition to surveys, a digital teacher journal and audio recordings were maintained to document class discussions and observations. In addition to the post-survey, student-written reflections were collected via Google Docs at the conclusion of the study.

Procedures and Data Analysis

The study was conducted over a 10-week period, with a pre-survey administered at the start to gather baseline data on students' perceptions and motivation. The first week included an initial group discussion where students shared their perceived strengths and goals and engaged in a collaborative puzzle activity. The activity required the entire class to work collaboratively on a shared task, allowing the teacher to observe their collective motivation and teamwork skills. The original growth mindset initiative was not well received by students, prompting the teacher to adjust the focus of the action research to address their needs better.

A new class discussion was initiated where the issue of perceived apathy in the classroom and its negative impact on the learning environment was discussed. Students were then asked to brainstorm rewards they would be motivated to work for all ideas written on the board. Students suggested incentives, and the teacher selected feasible options: seat choice, one week with no homework, and a class party with a movie. Clear criteria were established for earning rewards: full participation from the class, with the expectation that all students contribute to the learning experience, no zeros on homework (with partial credit allowed for late submissions), and a 75% class average on assessments. Progress was evaluated at midterm and quarter end. Participation and homework completion were tracked weekly.

At the study's conclusion, a post-survey was administered. Students also submitted written reflections via Google Docs to evaluate changes in their perceptions. The puzzle activity was repeated and observed for teacher observations. Data from pre/post surveys, using the Likert scale, and qualitative responses were analyzed for shifts in motivation and engagement. This combination of self-reported data, behavioral tracking, and reflection provided a well-rounded measure of the intervention's effectiveness.

Results

This action research explored the impact of granting students autonomy when choosing classroom rewards on their motivation, engagement, and academic performance. The findings demonstrate that this strategy positively influenced students' confidence, interest in math, and overall classroom experience, aligning with the study's goal of reducing apathy and closing achievement gaps. Survey data showed a notable increase in self-efficacy, with an average gain of +6.6 points in students' confidence in their academic abilities.

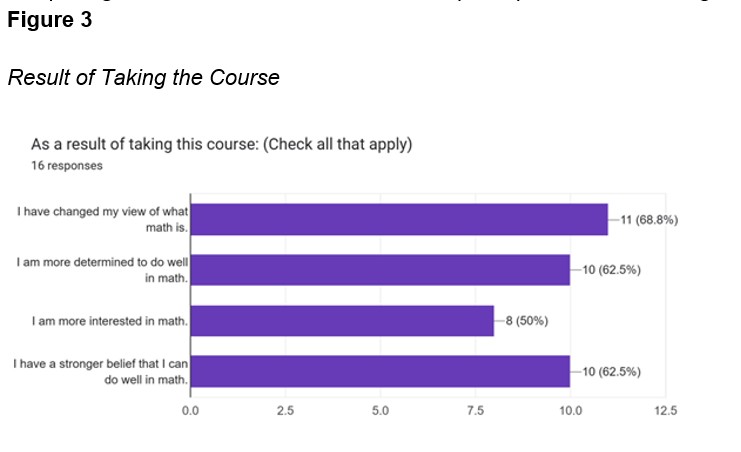

Additionally, 62.5% of students reported a stronger belief in their ability to succeed and expressed greater determination to do well in math. One student reflected, “I used to hate math and thought the class was stressful, but now I like the class and the teacher. I hope to focus more and get an A.”

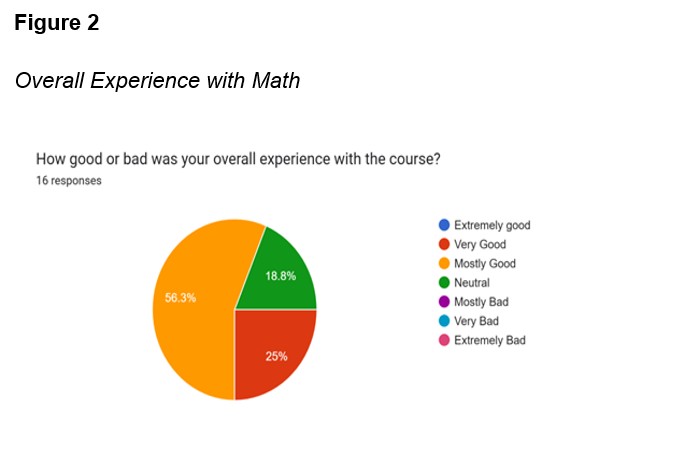

Interest in math also improved, with 50% of students indicating they were more engaged by the end of the program. Engagement can be attributed to the incentive structure that tied student-driven rewards to class goals. As one student shared, "When the year started, I was annoyed to come to class. Now, it is totally different—we worked hard for the class prize, and it made math fun." Overall, 81.3% of students rated their course experience as either "Mostly Good" or "Very Good" (Figure 2), showing broad satisfaction with the intervention.

Although the average growth mindset score declined slightly by -1.2 points, this may reflect greater realism rather than disengagement. Interestingly, 68.8% of students still reported a positive shift in how they view math (Figure 3). A student explained, "In the beginning of math, I felt the whole class was lost and confused, not many people were paying attention, the class was basically asleep…. The class has made so much growth and improvement and it wasn't because the teaching style was different, it was the mindset that was different. We all worked super hard and got a reward at the end."

An unexpected yet meaningful outcome of the intervention emerged during the repeated puzzle activity at the end of the study. Unlike the first attempt, where many students left before completing the task, this time, the entire class participated in assembling the puzzle.

This activity revealed a sense of community and collaboration that had not been present earlier in the school year. One student enthusiastically stated, "We put the puzzle together! Last time, everyone left." This moment highlighted a collective achievement and marked a significant shift in classroom culture.

These results support the conclusion that autonomy-driven extrinsic motivation can enhance student confidence and engagement, even among students with limited initial interest or belief in their ability to succeed. The data supports the theory that when students feel more capable and have their efforts recognized through rewards, their engagement levels rise. Behavioral interventions, such as goal setting and reward milestones, created a reinforcement loop whereby students' achievements led to positive emotions and increased motivation to stay engaged with the material.

Implications

The findings from this study align with the literature, particularly David Geary’s theory and Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which emphasize the importance of building extrinsic motivation when intrinsic motivation is lacking. Geary’s evolutionary perspective suggests that students are not naturally motivated to learn biologically secondary skills, such as math, and therefore extrinsic motivation can play a crucial role in their academic development. Similarly, SDT emphasizes the value of autonomous extrinsic motivation, which is linked to increased engagement and academic success when students lack intrinsic motivation.

The data from this study demonstrates that allowing students autonomy in selecting their rewards impacted their motivation and engagement. For instance, 62.5% of students reported a stronger belief in their ability to succeed in math, and half of them expressed increased interest in the subject. These findings support the idea that when carefully designed to promote competence and relatedness, autonomous extrinsic rewards can effectively foster motivation, even without intrinsic interest.

These findings are important for educators, as they highlight that extrinsic motivation, when aligned with students' needs for autonomy, is not only beneficial but necessary for fostering engagement. Educators should continue to focus on creating environments where students feel capable, supported, and rewarded for their efforts, particularly when intrinsic motivation has not yet developed.

References

De Kraker-Pauw, van Wesel, F., Krabbendam, L., & van Atteveldt, N. (2022). Students’ Beliefs About the Nature of Intelligence (Mindset). Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(4), 607–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558420967113

Dweck, C.S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Geary, D., Xu, K.M. Evolution of Self-Awareness and the Cultural Emergence of Academic and Non-academic Self-Concepts. Educ Psychol Rev 34, 2323–2349 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-022-09669-2

Mabry, T. (2022). Perspective! The secret to student motivation and success. CORWIN.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Watson, A. C. (2019). Learning Grows. Rowman & Littlefield.

Xu, K. M., Coertjens, S., Lespiau, F., Ouwehand, K., Korpershoek, H., Paas, F., & Geary, D. C. (2024). An Evolutionary Approach to Motivation and Learning: Differentiating Biologically Primary and Secondary Knowledge. Educational Psychology Review, 36(2), 45-. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09880-3