Rationale

Comprehensive school counseling programs need to carefully assess and tailor interventions to meet the student populations’ needs. Unfortunately, the needs of high achieving adolescents in accelerated curricula are often not prioritized in research or practice and many of the universal programs geared towards the general population lack empirical support for their effectiveness with high achieving students. Therefore, this research can help inform school-based mental health professionals work with high achieving students and extend our understanding of effective treatment interventions available to address this populations unique mental health needs.

Context

Participants in this study were approximately 150 grade 9 high school students enrolled in one diverse early college high school program in South Florida. This early college high school is the only public, accelerated pre-collegiate program with all of its students working towards a cost-free bachelor’s degree and high school diploma simultaneously. Students enrolled in the program are uniquely advanced, with exceedingly high academic achievement, advanced maturity, and personal initiative. The research was conducted during the Steps 2 Success class and delivered by the 9th grade school counselor as a part of the schools comprehensive school counseling program.

Supportive Literature

High Achieving Students and Mental Health

A growing body of literature indicates that high achieving students are not immune to mental health distress and may have unmet social-emotional needs (Kennedy & Farley, 2017; Suldo et al., 2018). Yet, positive stereotyping surrounding the high achieving population (Colangelo & Wood, 2015), had led to parents, educators, and counselors to overlook or not even recognize that these students need support (Kennedy & Farley, 2017). Positive stereotyping also contributes to high achieving students not expressing their needs (Peterson, 2009) and maintaining a façade of invincibility (Peterson & Lorimer, 2011).

High Achieving Students and Perfectionism

Perfectionism is a frequently cited trait in high achieving individuals (Horwitz et al., 2012; Mofield & Parker-Peters, 2015; Papadopoulos, 2020) and is one of the most common concerns of parents with high achieving children (Stricker et al., 2019). Damian and colleagues (2017) study was the first to provide supportive evidence showing that high academic achievement is a common factor in developing perfectionism. For example, these students’ high abilities may prevent opportunities to experience failure, indicating that perfection is achievable (Damian et al., 2017). Then based on these early experiences, the students believe perfection is the expected standard (Speirs Neumeister, 2018). Perfectionism plays a critical role in mental health and has been linked to depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Limburg et al., 2017). Perfectionism may also indirectly influence maladaptive coping skills and behaviors that enhance and maintain stress (Dang et al., 2020; Hewitt & Flett, 2003).

Overcoming Perfectionism

The study classroom-based intervention was adapted and modified from the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Perfectionism (CBT-P) small group intervention (Bendit, 2022; Handley et al., 2015). Lessons included understanding perfectionism, motivation to change, challenging perfectionist beliefs through behavioral experiments and thought diaries, decreasing procrastination and self-criticism, and building self-compassion (Bendit, 2022; Handley et al., 2015). A number of studies within different settings and formats evaluated the treatment efficacy of CBT-P (Egan et al., 2014; Handley et al., 2015; Bendit, 2022), however, only one study was with early college high school students. Additionally, none of the studies examined the efficacy of CBT-P within this population when delivered as a universal intervention. A classroom approach has the potential to reach even more high achieving students, specifically those who are more prone not to seek help or self-disclose mental health concerns (Dang et al., 2020; Hewitt & Flett, 2002). Therefore, this study will expand this line of research by exploring the impacts of CBT-P as a universal classroom-based intervention.

Research Methods

The present study utilized a mixed methods research design to examine the impact of a classroom-based perfectionism intervention on grade 9 high achieving early college high school students’ level of perfectionism and wellbeing. The school counselor was trained by this researcher on how to deliver the intervention and study protocols prior to the start of the study. Students enrolled in the Steps 2 Success Course on “A day” were selected to receive the study intervention.

Quantitative data was collected using the Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS). The CAPS is a 22-item measure designed to assess self-oriented perfectionism (i.e., exceedingly high personal standards) and socially prescribed perfectionism (i.e., the perception or belief that others demand perfection from the self) in children and adolescents up to age 18 with a minimum of grade 3 reading level.

Students completed the CAPS one week prior to the start of the classroom intervention. The study intervention was delivered by the school counselor and consisted of four 60-minute classroom lessons spaced one week apart. Students then completed the CAPS again at the end of the study. Qualitative data was collected each week and included student lesson reflection logs and observation by the school counselor in the form of notes on student engagement and intervention material and anecdotes recorded in their reflection journal. Qualitative data will be coded and analyzed for themes that help to address the research question. The CAPS data in conjunction with the themes identified from the reflection logs will be used to evaluate the impact of the targeted classroom-based perfectionism intervention on grade 9 students level of perfectionism and personal wellbeing.

Results

- What is the difference in self-oriented perfectionism between grade 9 students who participated in the Overcoming Perfectionism lessons and those who did not?

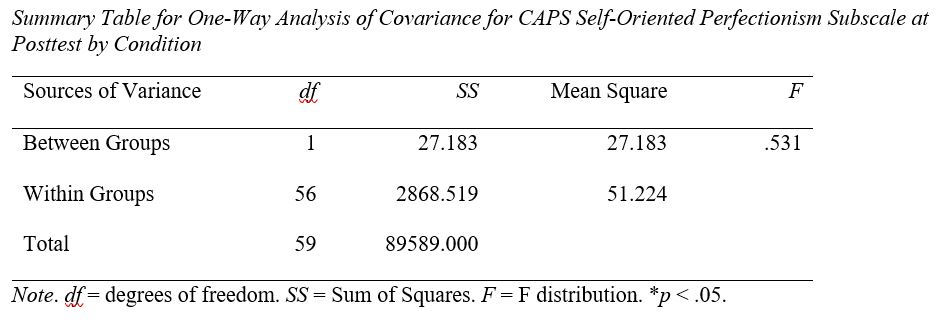

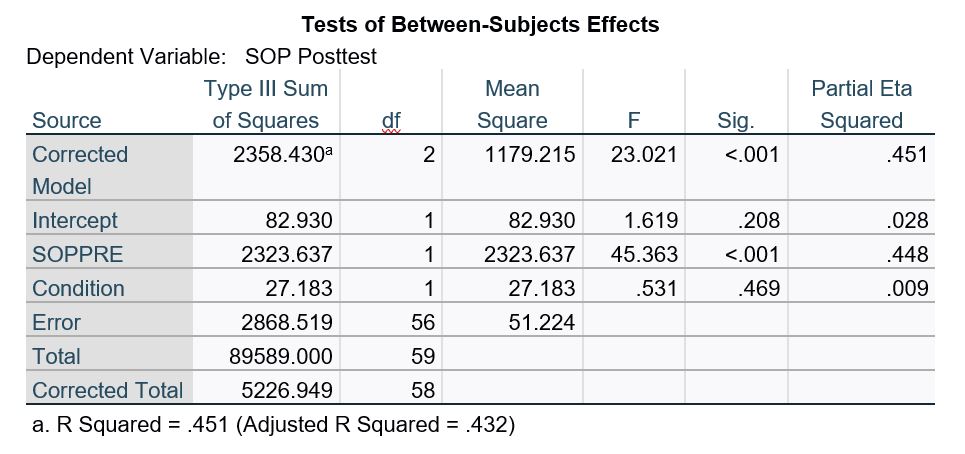

- The researcher used ANCOVA to test the hypothesis that students receiving the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (treatment group; n

= 47) would evidence a decrease in self-oriented perfectionism compared to students who did not receive the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (comparison;

n

= 12). The researcher controlled for differences in the students’ self-oriented perfectionism prior to the intervention by using the student's self-oriented perfectionism pretest scores as a covariate and group as a factor. Results from the ANCOVA revealed no statistically significant difference [F (1, 56) = .531,

p

= .469] between treatment and comparison groups.

- The researcher used ANCOVA to test the hypothesis that students receiving the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (treatment group; n

= 47) would evidence a decrease in self-oriented perfectionism compared to students who did not receive the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (comparison;

n

= 12). The researcher controlled for differences in the students’ self-oriented perfectionism prior to the intervention by using the student's self-oriented perfectionism pretest scores as a covariate and group as a factor. Results from the ANCOVA revealed no statistically significant difference [F (1, 56) = .531,

p

= .469] between treatment and comparison groups.

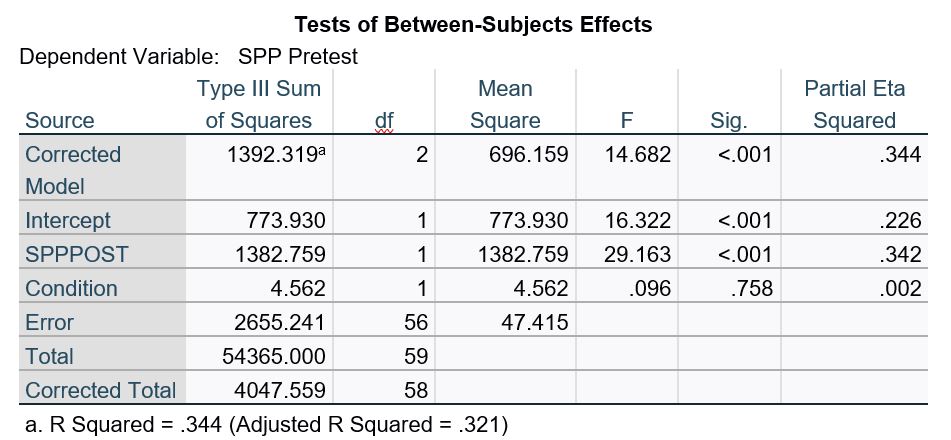

- What is the difference in socially prescribed perfectionism between grade 9 students who participated in the Overcoming Perfectionism lessons and those who did not?

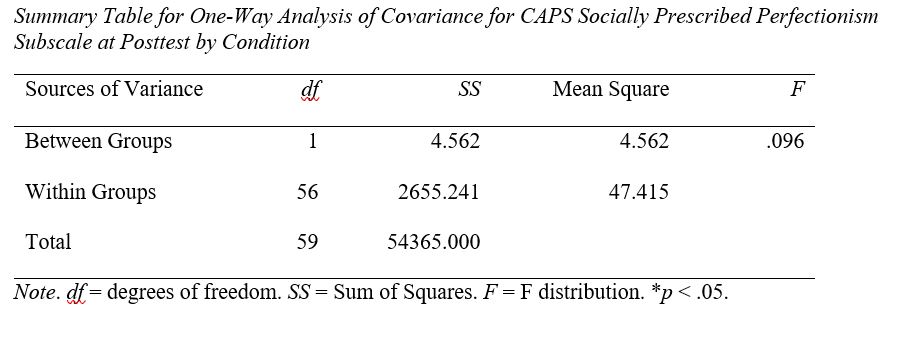

- The researcher used ANCOVA to test the hypothesis that students receiving the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (treatment group; n = 47) would evidence a decrease in socially prescribed perfectionism compared to students who did not receive the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (comparison; n = 12). The researcher controlled for differences in the students’ socially prescribed perfectionism prior to the intervention by using the student's socially prescribed perfectionism pretest scores as a covariate and group as a factor. Results from the ANCOVA revealed no statistically significant difference [F (1, 56) = .096, p = .758] between treatment and comparison groups.

- The researcher used ANCOVA to test the hypothesis that students receiving the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (treatment group; n = 47) would evidence a decrease in socially prescribed perfectionism compared to students who did not receive the Overcoming Perfectionism classroom lessons (comparison; n = 12). The researcher controlled for differences in the students’ socially prescribed perfectionism prior to the intervention by using the student's socially prescribed perfectionism pretest scores as a covariate and group as a factor. Results from the ANCOVA revealed no statistically significant difference [F (1, 56) = .096, p = .758] between treatment and comparison groups.

- How does the Overcoming Perfectionism lessons provided to grade 9 students change their personal mental health habits?

- Results of the weekly reflection logs helped to assess and evaluate the program. Participants indicated that they were most likely to adjust/reflect on their perfectionistic thinking patterns (32%), self-critical thoughts (25%), and procrastination behaviors (21%) after receiving the Overcoming Procrastination Lessons. Additionally, 51% of students wanted to learn additional strategies to manage perfectionism and their emotional health, however, approximately 12% of responses indicated themes of control in which participants wanted strategies that completely prevent perfectionism from happening. For example, some participants wanted to work on preventing perfectionistic thinking patterns such as, “how to control feelings of shame from happening” and to “learn how to prevent overthinking”. While others wanted to learn more about “how to avoid these types of behaviors” or “avoid being a perfectionist”.

Implications

Addressing the nation’s growing mental health problem among adolescents (CDC, 2020) is a priority in educational settings. Despite findings from this study being inconsistent with previous research employing CBT interventions to decrease perfectionism (Handley et al., 2015; Steele et al., 2013), this study advances the literature as the first to assess this counseling intervention in a classroom setting. Future studies should continue to explore the impact of the Overcoming Perfectionism program, as students with higher levels of perfectionism are less likely to seek formal support and are more likely to suffer in silence (Zeifman et al., 2015). Additionally, attrition challenges contributed to the small sample size, and missing data can make it more challenging to carry out a true intention to treat analysis (Dumville et al., 2006).

The literature on perfectionism demonstrates a strong association with dichotomous thinking patterns, underachievement, and anxiety (Kennedy & Farley, 2018). The Overcoming Perfectionism lessons specifically addressed these associations and underlying concerns through various treatment strategies. However, future iterations of the program may consider implementing more experiential exercises and skills as approximately 70% of students indicated they wanted to learn even more about perfectionism and emotional health strategies. Additionally, many participants appear to struggle with all or nothing thinking and/or high expectations for controlling or preventing perfectionism, which appears to demonstrate that these students need more strategies that challenge underlying rigidity and perfectionistic thinking patterns that may prolong or worsen distress (Flett & Hewitt, 2013).

References

Bendit, A. L. (2022). The effects of CBT on perfectionism, help-seeking, negative affectivity, and social-emotional well-being on early college high school students (Order No. 29261733). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2709946390).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020, June 15). Data and Statistics on Children’s Mental health https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html

Colangelo, N., & Wood, S. M. (2015). Counseling the gifted: Past, present, and future directions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(2), 133-142. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00189.x

Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru-Subtirica, O., & Baban, A. (2017). On the development of perfectionism: The longitudinal role of academic achievement and academic efficacy. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 565-577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12261

Dang, S. S., Quesnel, A. D., Hewitt, L. P., Flett, L. G., & Deng, X. (2020). Perfectionistic traits and self-presentation are associated with negative attitudes and concerns about seeking professional psychological help. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 27(5), 621-629. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2450

Dumville, J. C., Torgerson, D. J., & Hewitt, C. E. (2006). Reporting attrition in randomized controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(1), 969–971. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7547.969

Egan, S. J., van Noort, E., Chee, A., Kane, R. T., Hoiles, K. J., Shafran, R., & Wade, T. D. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of face to face versus pure online self-help cognitive behavioral treatment for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 107-113. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.009

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2013). Disguised distress in children and adolescents “flying under the radar”: Why psychological problems are underestimated and how schools must respond. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 12-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468845

Handley, A. K., Egan, S. J., Kane, R. T., & Rees, C. S. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of group cognitive behavioural therapy for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 68(1), 37-47. https://dx.doi.org/10/1016/j.brat.2015.02.006

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Habke, M., Parkin, M., Lam, R. W., McMurtry, B., Ediger, E., Fairlie, P., & Stein, M. B. (2003). The interpersonal expression of perfection: Perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1303-1325. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1303

Horwitz, G. A., McGuire, T., Busby, R. D., Eisenberg, D., Zheng, K., Pistorello, J., Albucher, R., Coryell, W., & Jeremy, J. T., & Fisher, A. P. (2012). High achieving students and their experience of the pursuit of academic excellence. ISEP International Symposium, 475-499.

Kennedy, K., & Farley, J. (2017). Counseling gifted students: School-based considerations and strategies. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 10(3), 361-367. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2018336194

Limburg, K., Watson, H. J., Hagger, M. S., & Egan, S. J. (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301-1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.2245

Mofield, L. E., & Parker-Peters, M. (2015). Multidimensional perfectionism within gifted suburban adolescents: An exploration of typology and comparisons of samples. Roeper Review, 37(2), 97-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2015.1008663

Peterson, J. S. (2009). Myth 17: Gifted and talented individuals do not have unique social and emotional needs. Gift Child Quarterly, 53(4), 280-282 https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986209346946

Peterson, J. S., & Lorimer, M. (2011). Student response to a small-group affective curriculum in a school for gifted children. Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(3), 167-180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986211412770

Papadopoulos, D. (2020). Psychological framework for gifted children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development: A review of the recent literature and implications. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young, 8(1), 305-323. https://doi.org/10.17478/jegys.6666308

Speirs Neumeister, K. L. (2018). Perfectionism in gifted students. In J. Stoeber (Ed.), The psychology of perfectionism: Theory, research, applications (pp. 134–154). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315536255

Steele, A. L., Waite, S., Egan, S. J., Finnigan, J., Handley, A., & Wade, T. D. (2013). Psychoeducation and group cognitive behavioral therapy for clinical perfectionism: A case-series evaluation. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(2), 129-143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465812000628

Stricker, J., Buecker, S., Schneider, M., Preckel, F. (2019). Intellectual giftedness and multidimensional perfectionism: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 391-414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648=019-09504-1

Suldo, S. M., O’Brennan, L. M., Storey, E. D., & Shaunessy-Dedrick, E. (2018). “But I’ve never had to study or get help before!”: Supporting high school students in accelerated courses. National Association of School Psychologists Communiqué, 46(6), 18-21. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED602891.pdf

Zeifman, J. R., Atkey, K. S., Young, E. R., Flett, L. G., Hewitt, L. P., & Goldberg, O. J. (2015). Perfectionism and self-stigma for seeking psychological help among high school students. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 30(4), 273-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573515594372